At the heart of our worship and how we praise God is music. Most churches, indeed most religions set a great deal of store by the importance of music.

We begin our Annual Summer Music Festival today, and in recognition of this celebration of the musical gifts in our midst, it is important to trace some Biblical and Theological themes which underscore the significance of music in our life.

A connection in today’s Gospel reading:

St Mark’s Gospel is underway. We’re in the corn-fields of rural Galilee, and Jesus’s disciples are doing what anyone might do, plucking an ear of corn. Jesus’s detractors, keen to catch this band out, presumably whilst in conversation, or debate, challenge the picking of corn – as an infringement of the Sabbath Laws. A nit-picking way to inflame the discussion. Jesus gives it back with both barrels though.

Jesus compares himself, and his disciples, with King David, and his companions. Out of hunger David and his crew ate what should have remained on the altar as a sacrifice – the Shew Bread in the sanctuary, but they ate it out of need. From this Jesus pronounces very solemnly, and with the sanction of his ancestor David himself – The Sabbath was made for man – not man for the Sabbath.

The passage continues with Jesus defying the Sabbath, or redefining the significance of the Sabbath law, you can argue for either.

Key here for us now is the association of Jesus himself with his ancestor David.

There are perhaps three strands to this bow, or three strings to this lyre.

If we look at King David’s life as whole, what can we tell?

A very large proportion of the Hebrew Bible is associated with David. The best part of 51 Chapters of the History Texts: I Sam, I Kings, I Chronicles. The Psalter is known also the Book of the Psalms of David. There are exactly 150. 73 of these have in the superscription that they are as Psalm of David and other sources suggest at least another two are by him.

The Church has used Psalms since before the NT was written. You might think that is funny thing to say, but we know from most of the records of the Last Supper, that before Jesus and his disciples made their way to the Garden of Gethsemane, they sang a Psalm. Given that Jews to this day sing Pss 114-118 during the Passover meal, it’s probable it was one or all of these and most probably the last.

St Paul, the first writer of the NT speaks of the word of God dwelling in the hearts of the faithful richly and to that end he exhorts the Colossians to “sing Psalms and spiritual songs with thankfulness in your hearts.” The Psalms were Jesus’s own hymn book. He quotes them constantly. Psalm 22 is in a sense the template for Jesus’s passion, whether meditation or prophecy, it shows the way of the suffering servant, that Our Lord’s ministry exemplified.

Scholars have pored over the Psalms for 200 years in a critical way, coming to different conclusions about their origin and authorship. Some are clearly very ancient, others date from the Babylonian exile. At some level, as a collection they are puzzle – certainly in terms of how they are grouped. In his commentary on Psalm 150 Augustine said “The sequence of the Psalms seems to me to contain the secret of a mighty mystery, but its meaning has not been revealed to me.”

They have different styles and purposes, either personal address to God, or a description of suffering. There is some cursing, there is some confessing, there are songs of thanksgiving and songs of the pilgrims going up to Jerusalem, and there are Psalms relating directly to monarchy, and within these latter two at least are tantalising expressions of what worship in Temple.

This poetic outpouring from the pen of the shepherd-boy-turned-renegade-turned-King, has behind it several strings.

David and Saul had a very complicated relationship. Before they even meet, David as a child has been appointed to replace Saul, who had lost God’s favour. He then kills Goliath, and becomes a part of the court. Saul, whose blessing has departed is afflicted by mental frenzy, the only one who can calm him is the lyre playing shepherd boy.

In an age more conscious of the power imbalances between a deranged King and a child-musician in his entourage, it is hard to know if the soothing music of the child is benign, when it seems to be all that protects the boy David from assault.

The love that Saul has for David is questionable. And the friendship between Saul’s son Jonathan with David begs questions. The two friends seem bound together as much by a common fear of Saul as by a bond – “surpassing the love of women”. Inevitably this causes speculation in modern scholarship.

The death of Saul and Jonathan, causes David deep agony, immortalising the words “How are the mighty fallen, and the weapons of war perished.”

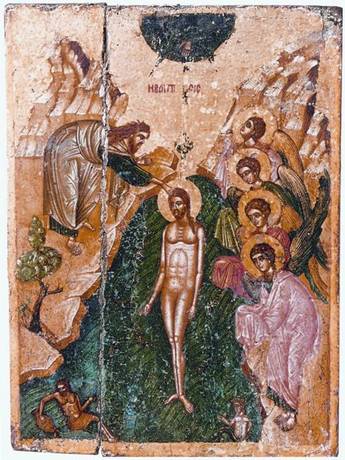

David’s excesses do not stop there. In due course he brings the Ark from the coast to his new capital, Jerusalem. Many of the instruments which are listed in Psalm 150, are recounted as having been played. David is captivated by the Spirit of the Lord, and he dances manically before it. David’s wife, Michal, the daughter of Saul, comes to David and berates him for this vulgar and shameless display. He is proud of having danced the Ark. Michal is unimpressed. But David’s being intoxicated in this way stokes Michal’s contempt for her husband. David the hero, who has conquered all before him, is unable to capture the heart of his own wife.

David introduces music, dancing and spiritual intensity into the worship of Israel’s God. His legacy is still known day by day in the worship of the Church. The 150 psalms are said or sung in the course of month. In Lent in the Orthodox Church the whole Psalter is said in the course of 7 days one week! That’s a lot of chanting.

Our own Plain chant which punctuates our service is almost entirely drawn from the Psalter.

David was the bad-boy rock star of the OT, as we get a sense of in today’s Gospel.

Let the last words be his in his final Psalm:

Praise the Lord in his sanctuary, praise him for his excellent greatness…Praise him with the trumpet, praise him with the lute and harp, praise him with the timbrel and dances, praise him with the strings and pipe, praise him with the sounding cymbals, let everything that breathes praise the Lord.