In today’s first lesson, Micah hears the nations of the world saying: Come, and let us go up to the mountain of the Lord, …we will walk in his paths: for the law shall go forth of Zion, and the word of the Lord from Jerusalem.

We hold in mind the departed of this parish in War, so our minds and memories ponder current conflicts.

Might we, unusually perhaps on Remembrance Sunday, consider the Battle of Gaza of 31 October – 7 November 1917. It was the third of that year, a decisive year in WWI.

Let me introduce you to some of the key players, whose respective roles in this battle or on the international stage, help us gather its significance then and now.

First, General Sir Edmund, later Viscount Allenby, Commander of the British Forces of the Sinai and Palestine Campaign from 27 June 1917. He had served alongside General Haig on the Western front. A month after his arrival he received a telegram, telling him his only son had died in action in France.

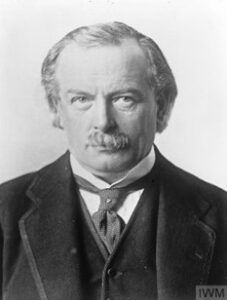

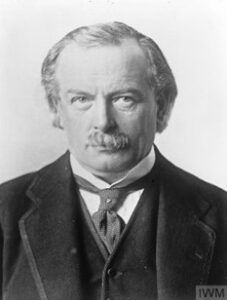

We all know something of David Lloyd George, the Welsh born British Prime Minister of WWI. One thing it might be important to hold on to, was something he told the Jewish Historical Society in 1925

I was brought up in a school where I was taught far more history of the Jews than about my own land. I could tell you all the kings of Israel. But I doubt if I could have named half a dozen of the Kings of England.

Four other less well known men need an introduction as well.

The first is the Shariff of Mecca and King of Hejaz, Hussein bin Ali al-Hashimi. His two sons would later reign as King Faizal of Iraq and King Abdullah of Jordan, the Hashemite Kingdoms founded after the War in Transjordan and Mesopotamia.

Chaim Weizmann 1874-1952 was a Russian born Jewish academic came to England 1904, where he taught Chemistry at Manchester University. He was a convinced Zionist, and from 1906 he conversed regularly with Arthur Balfour, nephew of Robert, Lord Salisbury and himself Salisbury’s successor as Prime Minister in the early 1900s, (hence Bob’s your uncle).

Sir Mark Sykes, a Lincolnshire baronet, whose childhood had been spent with his father travelling in the Middle East, an intriguing preparation for later diplomatic service in the Levant, which he loved.

The Great War, should have concluded by Xmas 1914. But as we know it went grinding on through 1915 and 1916 on all fronts and no end in sight.

Different political and diplomatic currents in the British establishment were seeking ways not only to end the war, but to secure Britain’s future post War interests. The creaking Ottoman Empire was perhaps an easy target for a short-term victory, and a long-term investment. It’s not clear how fixated the British were then on Iraqi oil, but they were determined on two things: to secure the Suez Canal; and secondly, to get one over on the French.

In the meanwhile, three parallel unaligned sets of conversations were taking place:

- Between the Shariff of Mecca and the British High Commissioner in Egypt Sir Henry MacMahon.

- Between Chaim Weizmann and Arthur Balfour (and through him with Lloyd George).

- And between Sykes, and a French counterpart in Levantine diplomacy Georges Picot.

MacMahon, along with Lawrence of Arabia, was stoking up the Shariff to rebel against the Ottomans, with the prize being the Arabian lands from the Arabian Peninsula to the Turkish border to the North, the Persian boundary to the East, and the Mediterranean to the West. It was never made explicit in the letters, but it was understood by the Shariff, that this included Palestine.

On the other hand, Balfour and Lloyd George were convinced by Zionism, with a baffling occlusion to the Arab presence in the Holy Land. Their fascination with Judaism was complex. It contained a blend of deep admiration, conviction of the Biblical Covenantal character of the people of Israel, a strange sense that that international Jewry somehow held the key, through its perceived internationalism, to facilitating an end to the War, and according to many historians, who have read the detailed correspondence, a lingering and unpleasant antisemitism.

And Sykes and Picot managed to negotiate France getting Syria and Lebanon while forfeiting any presence in Palestine, which would be held by an international mandate. They by then had secured Morocco as the Western buffer to Algeria, as compensation for loss of Egypt. The straight-line borders say it all in terms of how borders were drawn.

Let us trace the events of 1917. There are several elements of this story which are not edifying, which does not mean they should not be told. Remembrance is after all about honesty, humility and the desire for grace.

The Sinai front was showing signs of collapse. Lloyd George believed morale might be boosted at home if the cracks in the near East could be exploited. Ieper and Passchendaele were mud-bound and indecisive. The Spring of 1917 saw the first two battles of Gaza. The Ottomans held firm, despite heavy attack, but Allenby was despatched to drive a third onslaught on Gaza and from there to continue up the coast, driving the Turks into their homeland. Lloyd George needed a hero, and Allenby certainly cut the dash, for which the Prime Minister was hoping.

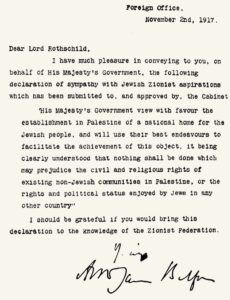

All through the same Summer of 2017 Balfour was finessing what was to become his Declaration. Lobbied by Weizmann, he honed its provisions and contents. Both imagined the establishment of a Jewish homeland in Palestine to be primarily a colony, sponsored by Britain. An essentially European enclave, upon which they both naturally agreed, but for the British Government, it would stand at the outer reaches of Suez, a bulwark against any attack on the Canal, the artery to India and the Far East. Balfour believed the energy and ingenuity of Jewish settlers would transform the barren terrain of Palestine, and he and Lloyd George were convinced of the destiny for which they were paving the way. Much of the 19th c had seen millenarian and Evangelical sectarians and Anglicans seeing mission amongst the Jews as a divinely ordained task. How much of this was conscious is hard to determine, but it was bound up with their vision. Plans were put before the cabinet in early October 2017, and two senior politicians stood robustly against it, Edwin Montagu – himself Jewish, but fiercely proud to be British and resistant to any notion of Judaism being a race apart rather than a religion; and Lord Curzon, who detected immediately the difficulty of a plan for a Jewish homeland, against the provision of support for Arab Palestinians. Curzon’s objections served to modify what would otherwise have been a declaration blind to the needs of the Arab population of Palestine. As Allenby embarked on command of the third Battle of Gaza 31 October 1917, the War Cabinet considered the final draft of Balfour’s proposed declaration.

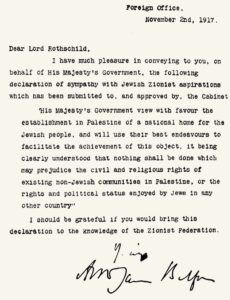

Having been agreed, Arthur Balfour wrote to Lord Rothschild

Dear Lord Rothschild, I have much pleasure in conveying to you, on behalf of his majesty’s government, the following declaration of Sympathy with Jewish Zionist aspirations, which has been submitted to and approved by the cabinet.

His Majesty’s Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.

I should be grateful if you would bring this declaration to the attention of the Zionist Federation. Yours Arthur Balfour.

The letter was published on 9 November 1917, but its contents were overshadowed by dramatic events in Russia. The Bolshevik uprising and arrival of Lenin caused Russia to begin disengagement with the War. As well as changing the axis of the conflict, weeks later, the Communists used their awareness of allied negotiations, to publish for the world to see, the contents of the Sykes-Picot discussions, which clarified the post war intentions of France and Britain. When by early 1918 the Shariff of Mecca was aware of the criss-cross of British double or even triple dealing, his disgust was apparent, and all Arabia with him, as their aspirations for control of Palestine, which seemed to have been promised in all sincerity by MacMahon, were decimated. As Oxford Jewish historian Avi Shlaim observed:

Thus, by a stroke of the imperial pen, the Promised Land became twice-promised. Even by the standards of Perfidious Albion, this was an extraordinary tale of double-dealing and betrayal.

None of this was before Allenby had won the third Battle of Gaza on 7 November 1917. The British press, hungry for good news, was delirious that at least on one front a British Expeditionary Force was at last making progress. The tone of the reporting was frightening to British Imperial officials. The Evening Standard declared Allenby a latter-day crusader. A section D notice had to be issued by the Ministry of Information, reminding Editors of the nearly 100 million Muslim subjects of the Empire and the march on Jerusalem was to defeat the Ottomans, and no echo of Mediaeval crusading. Nevertheless, following the Prime Minister’s wishes, Allenby made his way to Jerusalem. Military historians regard his achievement in taking Jerusalem remarkable, given the difficulty of the terrain and the complex supply lines for water and munitions.

However, Jerusalem had no military or strategic value, sitting way above the Levantine coast, in the Judaean hills. But its capture by Allenby on 8 December was the Christmas present Lloyd George needed. Huge advantage was gained by Allenby’s entry into Jerusalem. Unlike the preposterous arrival of the Kaiser in 1898 on horseback, dressed almost as a Crusader Knight at Sion Gate, as we see on the front of this order of service, Allenby dismounted from his stead and walked humbly into the city. The comparison of choreography was deliberate.

Allenby’s words to the inhabitants of Jerusalem struck an immediate chord with all who heard and read them:

Since your city is regarded with affection by the adherents of three of the great religions of mankind and its soil has been consecrated by the prayers and pilgrimages of multitudes of devout people of these three religions for many centuries, therefore, do I make it known to you that every sacred building, monument, shrine, traditional site, endowment, pious bequest, or customary place of prayer of whatsoever form of the three religions will be maintained and protected according to the existing customs and beliefs of those to whose faith they are sacred.

Guardians have been established at Bethlehem and on Rachel’s Tomb. The tomb at Hebron has been placed under exclusive Moslem control.

The hereditary custodians at the gates of the Holy Sepulchre have been requested to take up their accustomed duties in remembrance of the magnanimous act of the Caliph Omar, who protected that church.

With hindsight after Versailles, Balfour was able to say with regret:

The literal fulfilment of all our declarations is impossible partly because they are incompatible with each other and partly because they are incompatible with the facts.

On a day of remembering, perhaps to remember that 106 years after the three Battles of Gaza, conflict there now, stemmed from words half said, promises half kept, and visions half dreamed. Might we pray for forgiveness and healing, and all the more earnestly for peace?

Jesus prays in today’s Gospel for selfless love of others, Micah foresees all nations seeing God’s law coming forth from Zion transforming the world. May selflessness, characterise the pursuit of peace, and might the ultimate peace of Jerusalem, and God’s law shine in the hearts of all. Amen.